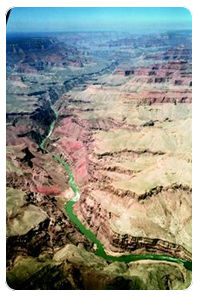

Anyone contemplating a flight through the Southwestern US will want to include the Grand Canyon in the itinerary. The full grandeur of this mile deep, 400 mile long, scenic wonder can only be truly appreciated when viewed from above. In addition to the spectacular canyon scenery, a visitor can discover hidden waterfalls, cool alpine meadows, and even a remote Indian village. Anyone contemplating a flight through the Southwestern US will want to include the Grand Canyon in the itinerary. The full grandeur of this mile deep, 400 mile long, scenic wonder can only be truly appreciated when viewed from above. In addition to the spectacular canyon scenery, a visitor can discover hidden waterfalls, cool alpine meadows, and even a remote Indian village.

Your enthusiasm for taking this scenic route may be dampened however, when you start flight planning. First, when plotting your route on the Las Vegas sectional, you'll notice it crosses a distinctive blue border that completely surrounds the canyon. Then you'll read an ominous warning printed on the chart, stating there are Special Federal Aviation Regulations (SFAR) in effect for the Grand Canyon. You may wonder if is it still possible to see this great natural wonder by air, or if these regulations force you to detour over less scenic terrain.

Relax. You can still sightsee the Grand Canyon in your airplane. The SFAR airspace does not mean you have to avoid the canyon; it simply means you must operate within certain constraints. Flying here is just no longer the airborne free-for-all it once was.

My first flight into the Grand Canyon was by helicopter—years before the airspace restrictions were even contemplated. We followed a commercial tour aircraft out of the Grand Canyon airport, staying at treetop level heading north towards the canyon rim. The gently up-sloping terrain effectively hid the canyon from view until the earth suddenly fell away from underneath us. Our altitude instantly went from 50 to 4,000 feet AGL as we crossed the canyon rim. My first flight into the Grand Canyon was by helicopter—years before the airspace restrictions were even contemplated. We followed a commercial tour aircraft out of the Grand Canyon airport, staying at treetop level heading north towards the canyon rim. The gently up-sloping terrain effectively hid the canyon from view until the earth suddenly fell away from underneath us. Our altitude instantly went from 50 to 4,000 feet AGL as we crossed the canyon rim.

We flew across the canyon towards the North Rim, marveling at the incredible landscape created by nature's powerful forces. Once over the center of the nine mile wide canyon, we turned westbound, following the sinuous Colorado River, nearly a mile below. We followed the river for several miles—until we were well out of sight of earthbound tourists—then descended down into the canyon. The canyon walls changed from white to blue-gray to brown to red as the various geologic layers, exposed by eons of erosion, stair-stepped down toward the Colorado. The pine trees populating the rim were replaced by cactus and sagebrush on the wide, flat esplanade deep inside the canyon.

The esplanade offered plenty of tempting landing areas to stop and enjoy our picnic lunch. We selected a spot on the north side of the river at the top of the inner gorge—where the canyon makes its final 1,000 foot plunge down to the churning Colorado. As the rotor blades slowly wound down after landing, we were enveloped in solitude. Only the buzz of insects and the occasional cry of a hawk circling overhead punctuated the muffled roar from the rapids far below. We found ourselves speaking in hushed voices, almost whispering, as we ate in this magnificent place.

After lunch, we fired up our helicopters, eager to continue the adventure. Hovering over the cliff's edge we pushed the nose over, diving into the inner gorge and to the very bottom of the Grand Canyon. Skimming over the whitecaps of the Colorado, the copilot stayed busy using the map to predict the river's twists and turns. We continued westbound until finding the distinctive blue-green water of Havasu Creek blending into the muddy Colorado.

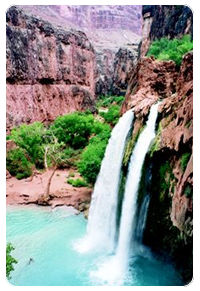

A sharp left turn had us following Havasu Creek upstream to where the thundering waterfalls of Havasu canyon came into view. First—and tallest—of the series of cataracts is Mooney Falls (named for the prospector who explored the river below the falls, not for the airplane). Two miles further up-canyon, we spotted the famous Havasu Falls. The minerals in the spring-fed Havasu Creek have built up travertine pools at the base of the falls and give the water its blue-green color. After touring the falls, we continued upstream, climbing to avoid disturbing the Havasupai Indian village of Supai located deep in the Grand Canyon. There is no road to this green oasis, the only access is on foot or horseback via a dusty trail—or by helicopter. A sharp left turn had us following Havasu Creek upstream to where the thundering waterfalls of Havasu canyon came into view. First—and tallest—of the series of cataracts is Mooney Falls (named for the prospector who explored the river below the falls, not for the airplane). Two miles further up-canyon, we spotted the famous Havasu Falls. The minerals in the spring-fed Havasu Creek have built up travertine pools at the base of the falls and give the water its blue-green color. After touring the falls, we continued upstream, climbing to avoid disturbing the Havasupai Indian village of Supai located deep in the Grand Canyon. There is no road to this green oasis, the only access is on foot or horseback via a dusty trail—or by helicopter.

Our helicopters made quick work of the nine miles to the trailhead as we exited the canyon and turned back toward base. On the way home, we talked about how spectacular the flight had been and promised ourselves we would do it again someday.

The SFAR airspace now in effect over the Grand Canyon makes it difficult to recreate this memorable flight in my Cessna, but it's not impossible. Though altitudes and available airspace are heavily restricted, there is still plenty of opportunity to tour the canyon legally and safely. Once you understand how the Grand Canyon airspace is divided, you too can follow the course of the Colorado, see the waterfalls of Havasu Creek, and even land and have a picnic overlooking the Colorado River.

The key to flying the Grand Canyon today is the Grand Canyon VFR Aeronautical Chart (General Aviation). Do not fly in the SFAR airspace below 14,500 feet without first studying this chart! Obtain a copy from your favorite aeronautical chart agent, or order the chart direct from NOAA at 1-800-638-8972 or on the Web at http://acc.nos.noaa.gov. This chart depicts how the airspace below 14,500 has been carved up, including the Flight Free Zones, restricted flight sectors, and transition corridors through the Flight Free Zones.

The flip side of the map depicts commercial tour operator routes throughout the canyon. The tour routes operate at lower altitudes than those allowed for general aviation, and are reserved only for tour operators specifically authorized by the FAA to operate within the SFAR. The heavy commercial sightseeing traffic in and over the canyon was a significant contributor to the perceived need to regulate this airspace back in the 1980s. The flip side of the map depicts commercial tour operator routes throughout the canyon. The tour routes operate at lower altitudes than those allowed for general aviation, and are reserved only for tour operators specifically authorized by the FAA to operate within the SFAR. The heavy commercial sightseeing traffic in and over the canyon was a significant contributor to the perceived need to regulate this airspace back in the 1980s.

Flight Free Zones mean just that, no aircraft—GA or commercial tour operator—allowed below 14,500 feet within the zones, period. These zones include the most heavily toured areas of the canyon, including the Grand Canyon Village and South Rim drive, as well as the North Rim's lodge and viewpoints. Also included are the popular hiking trails and campgrounds within the canyon. The idea behind these zones is to preserve the tranquility of the park by eliminating aircraft noise, though I think it would be impossible to hear our little 172 over the traffic noise at the crowded rim-side viewpoints.

Interspersed between the Flight Free Zones are four named flight corridors, allowing north-south traffic to cross the canyon. The corridors have hard altitudes assigned, the lowest being 10,500 feet southbound and 11,500 feet northbound. This is intended to keep you well above the commercial traffic operating in the same corridors a few thousand feet below. The Grand Canyon VFR chart conveniently lists latitude and longitude for each corridor's northern and southern end, allowing them to be programmed easily into your trusty GPS or LORAN. For the technologically challenged, the map also provides radial and DME fixes for these points, as well as the recommended magnetic heading for each route.

The remainder of Grand Canyon airspace is divided into five named Sectors, each with a different minimum altitude, ranging from a low 4,999 feet in the northeastern-most Sector to the highest floor of 9,999 feet near the noise sensitive tourist centers. Be especially vigilant for tour operators when using the lower Sectors, since the minimum altitudes there are lower than the published commercial tour route altitude, resulting in an overlap of operating altitudes.

Once you become familiar with these Sectors and corridors you can plan a spectacular Grand Canyon sightseeing flight without violating the SFAR. My favorite route runs from east to west—crossing the canyon several times—and allows me to fly at the lowest legal altitudes.

Approaching the Grand Canyon from the east, intercept the Little Colorado River Canyon at the 10,000 foot minimum altitude for the Supai Sector. Follow the deep, narrow canyon westbound as the Grand Canyon gradually fills the windscreen. As you enter the Grand Canyon, look straight down to see the muddy waters of the Little Colorado mixing with the deep green Colorado. Turning south over the Colorado, climb to 10,500 feet and intercept the Zuni corridor as it crosses the river. Looking west, passengers have an excellent view of the length of the canyon and the river snaking through its depths. The Zuni corridor ends just south of the South Rim of the canyon, where you turn west toward the Grand Canyon VORTAC.

The VORTAC is located at the Grand Canyon airport, so maintaining altitude will keep you well above the GCN Class D airspace. Use caution, as this is a very busy airport with a steady stream of air-tour operators arriving and departing. For a fast fuel stop I recommend skipping GCN in favor of Valle airport, 18 miles south. There is much less traffic at Valle (pronounced valley), fast service, and its location provides a more gradual descent and climb out from SFAR altitudes. As an added bonus, there is a restaurant across the street and a first rate aircraft museum on field. Call 520-635-5280 for more information. The VORTAC is located at the Grand Canyon airport, so maintaining altitude will keep you well above the GCN Class D airspace. Use caution, as this is a very busy airport with a steady stream of air-tour operators arriving and departing. For a fast fuel stop I recommend skipping GCN in favor of Valle airport, 18 miles south. There is much less traffic at Valle (pronounced valley), fast service, and its location provides a more gradual descent and climb out from SFAR altitudes. As an added bonus, there is a restaurant across the street and a first rate aircraft museum on field. Call 520-635-5280 for more information.

The next leg of this Grand Canyon scenic tour is flown at 11,500 feet as you cross the canyon rim northbound in the Dragon Corridor. Alert your passengers to the busy tourist center of Grand Canyon Village off the right wing as you approach the South Rim and to Hermit's Rest directly below as you cross the canyon rim. Approaching mid-canyon, look several miles to the right for the well-worn mule trail to Plateau Point on the edge of the inner gorge.

The North Rim of the Grand Canyon lies roughly 1,000 feet higher than the South Rim, so you will suddenly find yourself at 2,000 feet AGL after crossing the canyon's North Rim. Looking east, you might be able to pick out the rustic North Rim Lodge nestled in the pines at the canyons edge. Descend to 10,500 feet while arcing around the Flight Free Zone before entering the Fossil corridor southwest-bound. This corridor serves as a quick transition route to the waterfalls of Havasu Creek.

Continue three miles on the same heading beyond the west end of the Fossil corridor to the village of Supai. Look for the lush, green oasis in the bottom of the hot, dry canyon. Follow this green ribbon northwest toward the Colorado; the falls will be a few miles downstream of the village. The distinctive blue-green color of Havasu creek sharply contrasts with the red rock of the surrounding canyons. Its worth the trip to follow the canyon all the way back to the Colorado, to see this clear creek mixing with the turbid waters of the river. Stay on the south side of the Colorado to avoid the Flight Free Zone, which begins on the opposite bank. The center of Havasu canyon also marks the boundary between the Supai sectors 9,999 foot minimum altitude, and the 8,999 foot floor of the Diamond Creek Sector.

The confluence of Havasu Creek and the Colorado River is a convenient place to end our sightseeing tour. From this point you can exit the canyon northbound via the Tuckup corridor (Colorado City is the closest fuel stop), or head southeast through the Supai sector back to GCN or Valle. If your flight plan takes you to the southwest, watch for the ancient lava flow which fall's into the Colorado just west of the Toroweap Overlook Flight Free Zone. Kingman is the nearest airport with fuel in this direction.

Though I miss being able to descend down into the Grand Canyon, sightseeing within the SFAR airspace is still rewarding. More of the canyon is visible at the higher altitudes now required, actually improving the experience for passengers. I also appreciate the safety margin provided by the higher altitudes and the separation of general aviation from the intensive tour operator traffic. So don't view that blue border around the Grand Canyon as an obstacle. Rather, consider it an invitation to safe and orderly sightseeing of one of the greatest natural wonders on the planet.

Gerrit Paulsen lives in Albuquerque, NM, and has been flying the Southwest for over twenty years. He has amassed nearly 4000 flight hours, first as an Air Force helicopter flight engineer and now as pilot of the family Cessna 172M. Gerrit holds a Master's Degree in Aeronautical Science, specializing in Education. He is currently working as a Senior Instructional Designer for Lockheed Martin, developing classroom and flight simulator training lessons for Air Force helicopter pilots and crew members. |