|

|

|

Life on the Edge – Tuweep, AZ

|

|

The Grand Canyon's Most Spectacular Overlook

|

Story and photos by Mark Swint

If you’re a serious solitude seeker who doesn’t mind a little extra effort to achieve some peace and quite, then boy, do I have a spot for you! It is called Tuweep, and it lies on the north rim of the Grand Canyon on land known as the “Arizona Strip.” It is one of the most remote places in the United States, with one of the most spectacular views in the world. It takes an extra dose of adventurous spirit and the ability to put up with everything “primitive and rustic” to enjoy this adventure, but if you can make the effort the reward will be well worth the trip.

For most adventurers, Tuweep can only be accessed by one of three bone jarring, tooth rattling dirt roads, the shortest of which is 60 miles, and the longest a wearying 90 miles of dusty, rutted, sometimes impassable dirt. For this reason, Tuweep experiences far fewer visitors per year than any other site on the canyon. Happily, there is another way to visit Tuweep – by air.

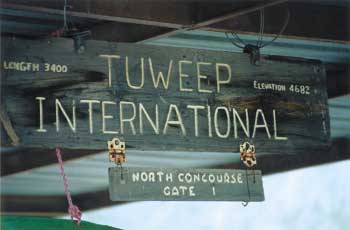

Just outside the National Park boundary in the Toroweap Valley lies the Tuweep airstrip (L50), a basic, though nicely groomed, dirt strip. Facilities are non-existent, save for a small covered area with two picnic tables at the north end of the strip. A sign on the awning proudly welcomes you to “Tuweep International Airport – concourse 1 gate 1.” The airstrip is located on Arizona State land, and is officially unattended and unmaintained. It is, however, unofficially maintained by Clair Roberts, the National Park Ranger assigned to Tuweep. Clair is an avid aviator, with a 180-hp Cessna 170 that he regularly flies from Tuweep. He is the pilot’s best friend at Tuweep, and – when not called away on park business – you can be assured of a friendly visit from him upon arrival. He makes an effort to meet and greet every single airplane that comes in (2 to 5 airplanes a month). Clair’s home is just a mile down the road from the airstrip, inside the park boundary, and he always has his radio with him. When he hears a plane overhead, he will turn on 122.9 to provide what basic wind info he can.

The Tuweep airstrip (N36°17.9 W113°04.2) lies just outside the Grand Canyon SFRA restricted airspace. Operations below 3,000 feet AGL are permitted in the SFRA within 3 miles of the airport when landing or departing. The elevation at the airport is 4682 feet. The strip is smooth dirt about 3,400 feet long. I took both the 185 and the Baron in and out of there, and the runway was no problem, even for the twin. Approach the airport from the north to remain outside the SFRA. Patterns should be flown to the west of the north/south (2/20) runway. Clair’s plane is parked on the south side, but transient planes should park on the north end.

A rough dirt road from Tuweep airport leads past the ranger station to the rim, some 6.3 miles away. About halfway to the rim the road splits, with the right fork leading to the Lava Falls Trail, while the left fork leads to the real attraction of Tuweep, the astounding Toroweap Overlook on the canyon rim. A rough dirt road from Tuweep airport leads past the ranger station to the rim, some 6.3 miles away. About halfway to the rim the road splits, with the right fork leading to the Lava Falls Trail, while the left fork leads to the real attraction of Tuweep, the astounding Toroweap Overlook on the canyon rim.

At the Toroweap Overlook, you can stand on the edge of a red sandstone cliff and look straight down for 3,000 feet to the Colorado River below. I will tell you right up front, this is not for wimps! There are no handrails or safety bars. Over the years, more than a few people have gone over the edge. I found that my personal limit was about three feet from the edge, though my buddy Mike Ballard, an avid skydiver, stood right on it! (I’ve always known skydivers were crazy, and I had to remind Mike he didn’t have his ‘chute on.) The cliff would be a base jumpers dream, though Clair says they really don’t have a problem with that because of the near impossibility of getting back out, plus base jumping is illegal in the canyon.

Toroweap’s first recorded non-Indian visitor was John Wesley Powell in 1870, on his futile search for two lost members of his 1869 Colorado River expedition. During his visit, Powell named most of the features in the valley and surrounding area. The word “Toroweap” is Paiute, meaning “dry” or “barren valley.” The word Tuweep refers to “the Earth.”

A visit to Tuweep and the Grand Canyon rim is neither for the faint hearted nor the out of shape. From the airstrip it is a lovely hike, but a hike nonetheless. It is possible that Clair will give you and your gear a ride to one of the campsites at the rim, but that is totally dependent on his schedule and availability. This is one trip that definitely benefits from a mountain bike, so those of you who could justify the hundreds of dollars for those fancy fold-up mountain bikes can take advantage of your investment here. While Clair is generally more than happy to provide rides down to the rim, day hikes from the airstrip can be a real joy as long as you are prepared. The number one rule for hiking in and around the Grand Canyon is to take water, water, and more water!

I have always thought of the Grand Canyon as a massive ditch carved by raging water through sandstone. Thrown into this mix, however, is a tremendous amount of volcanism, and nowhere is this more evident than from Toroweap Overlook. Looking directly across the canyon one can see, near the bottom, an outcropping of dark basalt from the side of the Supai Sandstone cliffs. This was actually an upwelling of lava that broke through the sandstone formation from the bottom up. Just upstream a couple miles, along the Tuckup Trail, there is another vertical basalt formation, or tube, called a breccia. During the mid 1900s this breccia was prospected, at great personal tribulation and effort, and apparently provided a respectable amount of gold, silver, lead, and other valuable minerals. The mining lease was held by one Henry Covington, who maintained a shaft through the breccia that was accessed by climbing down a 700-foot cliff. His mine was called Shepherd’s Folly, and it remained active until the late 1960s. I cannot begin to imagine the methods and effort he must have expended to get ore out of there and up the cliff-side to the plateau. Once there, he still had to get it somewhere it could be processed. Needless to say, Henry did not die a rich man.

About 150 yards to the west of the main overlook is another viewpoint that affords spectacular views of the famous Lava Falls. Lava Falls Rapids is rated a 10, the most difficult, on the international rapids rating system. This rapid is the standard by which all other rapids are graded. There is a standing wave plus a 35-foot fall across this monster rapid. In years past, boats were always taken out upstream and carried past this killer. Recently though, the professional guides that run the river have figured out a safe and exhilarating way to shoot the falls in their rafts. From high up on the overlook, you can hear the powerful river on a still day. About 150 yards to the west of the main overlook is another viewpoint that affords spectacular views of the famous Lava Falls. Lava Falls Rapids is rated a 10, the most difficult, on the international rapids rating system. This rapid is the standard by which all other rapids are graded. There is a standing wave plus a 35-foot fall across this monster rapid. In years past, boats were always taken out upstream and carried past this killer. Recently though, the professional guides that run the river have figured out a safe and exhilarating way to shoot the falls in their rafts. From high up on the overlook, you can hear the powerful river on a still day.

The large lava flow cascading down the north side of the canyon that created the Lava Falls Rapids is the Toroweap Lava Flow, which came down eons ago from Vulcan’s Throne, a volcanic cone on top of the plateau. This flow formed a massive dam on the river as it flowed into Prospect Canyon on the south side, ultimately forming a lake whose surface was almost 100 feet higher than present-day Lake Powell. The resulting lake was massive. Today, geologists studying the structure of Grand Canyon find not only ocean sediments from the primeval waters that laid down the eventual sandstone formations of the cliffs, but also lake sediments from the water backed up by this lava flow. John Wesley Powell’s description of the river below Tuweep and the volcanic walls that hem it in is most striking:

“What a conflict of water and fire there must have been here! Just imagine a river of molten lava running down into a river of melted snow. What a seething and boiling of the waters; what clouds of steam rolled into the heavens!”

Nearby, the Lava Falls Trail leads to the bottom of the Grand Canyon. A sign at the trailhead warns that it drops 2,500 feet to the river below in just a mile and a half. You can do the math, but the bottom line is the trail is very steep. There is absolutely no water and no shade along the way. In summer, the temperatures at the rim can hover over 100º, and temperatures down in the canyon top out over 110º. Additionally, the sides of the sandstone cliffs act as reflectors, magnifying the heat. A hike to the bottom should only be attempted by people in excellent physical shape. Much of Claire Roberts job, and that of the other rangers at the canyon, is the rescue of exhausted and dehydrated hikers who get down this deceptively short trail just fine, but can’t get back up. Again, the rule is bring water, water, and more water!

Before heading for Tuweep, you should call the Grand Canyon National Park dispatcher to leave a message for Clair Roberts (928-638-7805), he will call you back when he can. This little pre-coordination might result in a far more interesting trip for you. If Clair is available during your visit, take advantage of his offer for a tour. He has a deep love and depth of knowledge of the area. Clair takes great joy in being a very well versed tour guide; as he points out the remarkable geology, biology, and fascinating historical accounts, the area literally comes alive. He has a keen eye for spotting subtle artifacts and Indian evidence that the normal eye would miss. (I was surprised by how much archeological evidence existed at the campsites and around the rim.) As Claire gives you his tour, be sure he tells you about Greyhound rock. This is a place near the rim where two large sandstone boulders flank the road. Some years ago, a bus driver brought a Greyhound bus from back east with a load of school kids to see the overlook. They made it as far as those rocks, which happened to be one inch narrower that the bus. The bus ended up wedged between the rocks, and a considerable effort was expended extracting it from the vise. Before heading for Tuweep, you should call the Grand Canyon National Park dispatcher to leave a message for Clair Roberts (928-638-7805), he will call you back when he can. This little pre-coordination might result in a far more interesting trip for you. If Clair is available during your visit, take advantage of his offer for a tour. He has a deep love and depth of knowledge of the area. Clair takes great joy in being a very well versed tour guide; as he points out the remarkable geology, biology, and fascinating historical accounts, the area literally comes alive. He has a keen eye for spotting subtle artifacts and Indian evidence that the normal eye would miss. (I was surprised by how much archeological evidence existed at the campsites and around the rim.) As Claire gives you his tour, be sure he tells you about Greyhound rock. This is a place near the rim where two large sandstone boulders flank the road. Some years ago, a bus driver brought a Greyhound bus from back east with a load of school kids to see the overlook. They made it as far as those rocks, which happened to be one inch narrower that the bus. The bus ended up wedged between the rocks, and a considerable effort was expended extracting it from the vise.

There are two campgrounds right at the rim. One is immediately off the rim, and offers a few picnic tables and a composting outhouse. It is a lovely site, but not good for sleepwalkers! The other campsite is just back up the road – still at the rim, but set back a bit. It has a few more sites available. There are eleven campsites in all, and believe it or not, they quickly fill up in the summer on weekends. Even with miles and miles of dirt, the roads are passable for most vehicles, and a procession of campers and RVs can usually be observed at week’s end. There are no facilities of any kind at Tuweep, so bring everything you will need. Oh yes, and make sure that includes lots of film so you’ll have memories of your Grand Canyon adventure!

Spring and early summer is a wonderful time to visit the Grand Canyon. If there have been recent rains the desert and canyon rim literally explodes with wildflowers. Speaking of rain, the area averages a dry 11 inches per year. Though the mean temperature is a crisp 54°, summertime temperatures often reach over 100°, so density altitude calculations should be part of your flight planning. Though spring and fall are the most pleasant times to visit, the airstrip is open year-round. Two inches of snow fell on us when we camped there in January, but it was gone by midday. Snow rarely stays on the ground for too long, but it can get cold and windy in the winter. If you go there in the summer, remember to still bring a coat, because like all deserts, it gets cold at night!

Some pilots shy away from the Grand Canyon because of the restrictive SFRAs concerning over-flight of the canyon. While the highest altitude restrictions seem a bit overdone, the majority of the canyon can be seem from a much more reasonable altitude. Recently my son David and I flew over the canyon in our plane in compliance with the restrictions. David flies the canyon daily as a tour pilot, and he was surprised to see that the view from the higher altitude of the SFRA actually proved more expansive and breathtaking than from the lower altitudes at which tour operators fly. Incidentally, one of Claire Roberts’ jobs with the Park Service is to monitor air traffic and report planes that violate the airspace restrictions to the FAA, so don’t be fooled into thinking you can get away with flying in the same area as the commercial operators. Some pilots shy away from the Grand Canyon because of the restrictive SFRAs concerning over-flight of the canyon. While the highest altitude restrictions seem a bit overdone, the majority of the canyon can be seem from a much more reasonable altitude. Recently my son David and I flew over the canyon in our plane in compliance with the restrictions. David flies the canyon daily as a tour pilot, and he was surprised to see that the view from the higher altitude of the SFRA actually proved more expansive and breathtaking than from the lower altitudes at which tour operators fly. Incidentally, one of Claire Roberts’ jobs with the Park Service is to monitor air traffic and report planes that violate the airspace restrictions to the FAA, so don’t be fooled into thinking you can get away with flying in the same area as the commercial operators.

Regardless of the restrictions, flying to and around the Grand Canyon can be a rich and rewarding experience. From the wide variety of wildlife to the breathtaking views, there is something for everyone. Tuweep provides a unique window on this special place that just might be worth a one-day trip or multi-day campout - You decide. Either way, don’t miss out on this truly magnificent jewel of the Southwest.

|

FLYING TO TUWEEP

The airspace in and around the Grand Canyon is designated as a SFRA (Special Flight Rules Area). Details about the special rules can be found on the Grand Canyon VFR Aeronautical Chart (general aviation), which is a must if you plan a trip anywhere near the canyon. Just remember that there is one side of the chart for the tour operators, and a side for the rest of us! The Las Vegas Sectional shows the lateral boundaries to the restricted areas (the old SFAR 50-2 was removed from the FARs but the rules still apply), but there are no details. Using the Grand Canyon chart is the only way to safely and legally navigate this airspace. The airspace in and around the Grand Canyon is designated as a SFRA (Special Flight Rules Area). Details about the special rules can be found on the Grand Canyon VFR Aeronautical Chart (general aviation), which is a must if you plan a trip anywhere near the canyon. Just remember that there is one side of the chart for the tour operators, and a side for the rest of us! The Las Vegas Sectional shows the lateral boundaries to the restricted areas (the old SFAR 50-2 was removed from the FARs but the rules still apply), but there are no details. Using the Grand Canyon chart is the only way to safely and legally navigate this airspace.

In talking with Grand Canyon Park Ranger Clair Roberts, I got a better sense of the rational and history behind these restrictions. The initial limitations on the canyon were enacted not because of noise, but rather traffic congestion. One particularly horrific accident occurred in the 1950s when two full airliners collided over the canyon. Other midairs occurred, and as sightseeing traffic increased, so did concern for the safety of the canyon visitors. In 1987, there were 60,000 flight-seeing tours per year over the canyon. Various groups started voicing their concerns about safety, and yes, noise. Congress promised to study the matter. By 1997, the number of flights had doubled to 120,000 per year. Congress eventually set the limit of commercial flights over the canyon at 90,000 on a yearly basis. These slots are doled out among the various canyon operators, and today the canyon boasts a healthy, safe aerial tourist trade.

Tuweep Ranger Clair Roberts is maintaining a longstanding tradition of hospitality towards the aviators who visit Tuweep. This tradition has been going on since the forties, when the areas most famous and colorful Ranger, John Riffey, began his 38-year tenure along with his Super Cub “Pogo.” John was famous along the Arizona Strip for his warmth, as well as his sense of humor. Though he was stationed in the most remote place in the United States, he was not a loner. He loved people, and you could not visit the area without getting an invitation to his home for a meal, or even to spend the night! John would spend hours recounting the history of the area, and telling tales of its more colorful inhabitants. He loved to cook, and was always looking to make a breakfast of pancakes or waffles for visitors. One had to be careful though, because as a practical joker, John had a penchant for occasionally hiding a piece of flannel inside a pancake, just to watch his visitor’s reactions. He also had a proclivity for making up names. If a visitor asked the name of “that little yellow flower by the side of the road,” he would respond “that’s a ‘Near Roadie.” The red flower over there a little bit would be a “Far Roadie.” Indians that dwelt in the caves in the cliffs above his house were “Igaroadies.” Tuweep Ranger Clair Roberts is maintaining a longstanding tradition of hospitality towards the aviators who visit Tuweep. This tradition has been going on since the forties, when the areas most famous and colorful Ranger, John Riffey, began his 38-year tenure along with his Super Cub “Pogo.” John was famous along the Arizona Strip for his warmth, as well as his sense of humor. Though he was stationed in the most remote place in the United States, he was not a loner. He loved people, and you could not visit the area without getting an invitation to his home for a meal, or even to spend the night! John would spend hours recounting the history of the area, and telling tales of its more colorful inhabitants. He loved to cook, and was always looking to make a breakfast of pancakes or waffles for visitors. One had to be careful though, because as a practical joker, John had a penchant for occasionally hiding a piece of flannel inside a pancake, just to watch his visitor’s reactions. He also had a proclivity for making up names. If a visitor asked the name of “that little yellow flower by the side of the road,” he would respond “that’s a ‘Near Roadie.” The red flower over there a little bit would be a “Far Roadie.” Indians that dwelt in the caves in the cliffs above his house were “Igaroadies.”

John Riffey loved the area, and in the days before the SFRAs he could often be seen flying his beloved Pogo down the river right on the water! His time at Tuweep ended with a heart attack some years ago, and he is buried just south of the ranger station, east of the road. His gravestone contains no birth or death dates, but it does have an accurate representation of Pogo, with a correct N-number!

|

Mark Swint is a senior captain for United airlines, flying 767 and 757 aircraft based in LAX. For fun, he flies a Cessna C-185 and a Beech Baron B-55. Mark, a licensed A&P, also likes to restore and rebuild airplanes, including building a Pitts S-2E, rebuilding a C-170 and two C-185s. He is currently finishing a 1946 Aeronca 7AC. Mark has been a writer for many years, including a two-year stint in Hollywood and London working in the screenwriting business. He recently appeared on television in the travel industry Sep. 11 recovery ad campaign, featuring travel industry professionals echoing President Bush’s stirring words.

Mark has been married to his wife Peggy for 28 years, and they have four children - one of whom has chosen to follow in his footsteps. His 22-year-old son, David, currently flies tour groups over the Grand Canyon in C-402s for King Airlines out of Henderson, Nevada. |

Click here to return to the beginning of this article.  |

|