Story and Photos by Russell Munson

Have you ever been boring holes in the sky on a beautiful day, looked out at the horizon, and thought, “What if I just keep going?” If so, that thought is from your friend, Miss Adventure, knocking on the inside of your head. "Keep going," she says, "keep going. See what lies beyond your line of sight." Have you ever been boring holes in the sky on a beautiful day, looked out at the horizon, and thought, “What if I just keep going?” If so, that thought is from your friend, Miss Adventure, knocking on the inside of your head. "Keep going," she says, "keep going. See what lies beyond your line of sight."

Has that ever happened to you? Have you been tempted to set aside, at least for a while, your copy of, "What I Should Be Doing," and open, "What I’ve Always Wanted To Do?" This tantalizing desire to just keep going is the spirit of America’s most famous highway, Route 66. Even though the two-lane road was mostly paved over by interstate highways decades ago, it has nevertheless remained an international symbol of the spirit of the open road: in a word, freedom.

In his famous book, "The Grapes of Wrath," John Steinbeck called Route 66, "The Mother Road, the road of flight." The spirit of the open road is the same whether you drive or fly, but you see much more from the sky. As my own salute to The Mother Road, I flew over the entire path of the old highway mile by mile in my Piper Super Cub, and made a DVD called, "Flying Route 66." The best part of making the disc was to yield once again to the call of the open road, a call which has beckoned me for as long as I can remember, to which I have succumbed often in the past, and by which I hope to be swept away many times yet to come.

Route 66 was completed in 1926 extending 2400 miles from Chicago to Los Angeles. Fortunately for us pilots, Meigs Field on Chicago’s lakefront is very near the official beginning of Route 66 [and, hopefully, will remain so once the recent vandalism by Mayor Daley is reversed - Ed], and Santa Monica’s Clover Field, birthplace of the DC-3, is close to the Santa Monica Pier which marks the end of the highway.

The Midwest seems to start just south of Chicago. Once past Joliet, Illinois, heading southwest down Interstate 55, which rolls over the original roadbed of Route 66, farms proudly define the landscape as if big cities didn’t exist. On a clear day, the expanse of fertile land from horizon to horizon is staggering, monumental in its flatness on a scale that could never be grasped from an automobile. From 500 feet above the ground, though, the perspective is both intimate and grand.

Old Route 66 landmarks and artifacts soon come into view if you know what to look for: the magnificent courthouse in Pontiac, Illinois, an old grain shed by an interstate access road which once was Route 66, and the now by-passed small towns such as Chenoa, Lexington, and Towanda that lent their personalities to Route 66 and in so doing formed its character.

I avoid large cities. When approaching St. Louis on this route, I alter my path to stay east of the sprawling Class B airspace until I am far enough south to turn west skirting the southern edge of the wedding cake.

Interstate 44 covers the former Route 66 heading southwest out of St. Louis, and the terrain becomes a little higher and more rumpled further down the road. This might help explain why I’ve been delayed by weather more often than I feel I deserve in the area of southwest Missouri from Springfield to Joplin. Springfield, by the way, has six huge BUTTs (Big Ugly Television Towers) that range up to 2000 feet AGL about 20 miles east of town. This is no place to be milling around in bad visibility looking for a way out.

I may be one of the few pilots who actually doesn’t mind weather delays. That’s part of the adventure. One doesn’t fly a Super Cub to see how fast you can get somewhere. When the weather begins to drop, I study my sectional chart and Flight Guide to find the closest approximation of my ideal airport: a small town strip with a courtesy car close to a nice motel. With any luck I’ll be due for a Laundromat visit or an oil change, too, so the time grounded can be well spent. I carry a few books in my bag, seek out local non-chain restaurants, and try to keep current on the latest movies. With all of that in addition to regularly checking the weather, a day or two passes in what seems like 48 hours. I may be one of the few pilots who actually doesn’t mind weather delays. That’s part of the adventure. One doesn’t fly a Super Cub to see how fast you can get somewhere. When the weather begins to drop, I study my sectional chart and Flight Guide to find the closest approximation of my ideal airport: a small town strip with a courtesy car close to a nice motel. With any luck I’ll be due for a Laundromat visit or an oil change, too, so the time grounded can be well spent. I carry a few books in my bag, seek out local non-chain restaurants, and try to keep current on the latest movies. With all of that in addition to regularly checking the weather, a day or two passes in what seems like 48 hours.

West of Joplin, the original Route 66 nicks the southeast corner of Kansas for a few miles passing through Galena and Baxter Springs before crossing the Oklahoma border. Of the entire length of the original Route 66, Oklahoma has the longest stretch of two-lane highway still posted as Route 66. It spans more than half the state roughly alongside Interstate 44.

Whoever named the towns between the northeast corner of Oklahoma and Tulsa loved the sound of words. In this relatively short stretch of highway I flew over Quapaw, Dotyville, Narcissa, Bluejacket, Vinita, Catale, Bushyhead, Foyil, Verdigris, and Catoosa. I said each name aloud to myself, and wondered how it came to be. Poking along at 90 knots down low you have time for such thoughts.

The southwestern United States is my favorite place to fly. By the time I get to Oklahoma I feel like I’m at the front door. Oklahoma is not the Midwest, it’s not the South, and it’s not yet the West. It is the transition in a major change in terrain from the farmland of the Midwest to the rangeland and rugged beauty of the Southwest. Over some parts of Oklahoma I can see from my cockpit cattle ranches, farms, and oilrigs in one view. The rich, red soil of ploughed fields near Sayre was so unreal it looked like a giant Kodachrome.

Even the most diehard Okalahoma enthusiasts must admit that the seven giant, huge BUTTs eight to ten miles northeast of Wiley Post airport in Oklahoma City are a menacing sight to sky bums like me. They range up to 1645 feet above the ground. Along with numerous other shorter antennas, they form an unwelcoming picket line from south to north on the eastern side of the city, and very near to Route 66 after it swings south at Edmond. I usually keep well north of the city until past the beautiful Sundance airport, then head southwest to one of my favorite refueling stops, El Reno Municipal Airpark. The grass strip which parallels the paved north-south runway is kept in good condition, and Rick, the airport manager, is very knowledgeable, helpful, and an all around nice person. A new credit card operated self-help fuel pump is a great addition, and El Reno has a courtesy car, too.

If you’re in the neighborhood, stop at Clinton in western Oklahoma, to visit the Route 66 Museum. Clinton has a nice airport, again with a courtesy car.

"Flying Route 66" is actually a composite of several trips. There was too much to show than could be gathered in one trip. On my most recent trip last October, I took off from El Reno heading west when pressure from my morning cups of tea became rather urgent west of Amarillo, Texas. You know what I mean. A quick look at the sectional chart showed Oldham County airport at Vega, Texas, just ahead. There was no answer on the listed frequency of 122.9, but despite my rapidly increasing pain, I flew over the field to check the windsock, then turned downwind to land to the south, calling my position on each leg. I thought I was being a very responsible airman by flying a full pattern in my condition even though there was no traffic in sight, and none responding on the radio. On short final just over the numbers, I noticed the needle nose of a turbine ag-plane pointing my way on its final approach landing to the north downwind. He was further out than I was, but if we both kept going as we were, we would soon be on the same runway at the same time looking at each other. There was no way I could go around without having to change clothes later, and besides, as the dead guy says after the accident, "I had the right of way." I called again giving my position, and made plans to pull off onto the grass if the ag-plane didn’t see me. There would be plenty of time and space to do that safely, if necessary. Remember that a Super Cub lands at 43 miles per hour, and uses very little runway. About that time the cropduster started his go around. Thanks, Captain. I taxied quickly to the ramp, jumped out, and ran, not walked, to the nearest facility. Ag pilots are sharp aviators once they live through the first few seasons. I suspect that this fellow, coming in very low, saw me against the sky long before I saw him, and perhaps hoped that I would break off my approach to save him a couple of minutes. Ordinarily, I would have been happy to do so, but not just then. "Flying Route 66" is actually a composite of several trips. There was too much to show than could be gathered in one trip. On my most recent trip last October, I took off from El Reno heading west when pressure from my morning cups of tea became rather urgent west of Amarillo, Texas. You know what I mean. A quick look at the sectional chart showed Oldham County airport at Vega, Texas, just ahead. There was no answer on the listed frequency of 122.9, but despite my rapidly increasing pain, I flew over the field to check the windsock, then turned downwind to land to the south, calling my position on each leg. I thought I was being a very responsible airman by flying a full pattern in my condition even though there was no traffic in sight, and none responding on the radio. On short final just over the numbers, I noticed the needle nose of a turbine ag-plane pointing my way on its final approach landing to the north downwind. He was further out than I was, but if we both kept going as we were, we would soon be on the same runway at the same time looking at each other. There was no way I could go around without having to change clothes later, and besides, as the dead guy says after the accident, "I had the right of way." I called again giving my position, and made plans to pull off onto the grass if the ag-plane didn’t see me. There would be plenty of time and space to do that safely, if necessary. Remember that a Super Cub lands at 43 miles per hour, and uses very little runway. About that time the cropduster started his go around. Thanks, Captain. I taxied quickly to the ramp, jumped out, and ran, not walked, to the nearest facility. Ag pilots are sharp aviators once they live through the first few seasons. I suspect that this fellow, coming in very low, saw me against the sky long before I saw him, and perhaps hoped that I would break off my approach to save him a couple of minutes. Ordinarily, I would have been happy to do so, but not just then.

There is a reason New Mexico is called the Land of Enchantment. It combines cultural heritage and natural beauty to create an atmosphere that is sensed before it can be described. Flying Route 66, the border between panhandle Texas and New Mexico is the entrance to the Southwest. Glenrio, Texas, is split by the border. Now bypassed by Interstate 40, the tiny town is virtually extinct. Route 66 was the pulse of Glenrio before the interstate. I have been sorely tempted a couple of times to land on the wide street that was once The Mother Road. No one is around. But wisdom prevails, so I circle photographing the remains of a gas station, gift shop, and a motel whose sign once read, "Last Motel in Texas" when seen from the east, and, "First Motel in Texas" when seen from the west.

It has been said that at some time in their life, every traveler will pass through Tucumcari, New Mexico. I love this town. I am at heart a transient, and this town was built by transients for transients. Beginning as tent city for workers on the intercontinental railroad, Tucumcari is ideally located in the dead center of nowhere, which makes it a convenient place to stop for people on their way to somewhere. It is a small town, but has more than 1200 motel rooms. When I first started stopping for the night here some 30 years ago, there was a friendly Flight Service Station on the field, and several motels had courtesy cars parked out front. You just got the keys from the FSS or the lineman, and drove into town. The FSS is gone now, but this is still a good place to stop. Tucumcari Municipal has two long runways, one of which is usually pretty closely aligned with the wind, and plenty of tie-down spots. At 4065 feet elevation out in the wide open spaces, wind and density altitude are serious concerns here, as you Southwestern pilots know.

On my last stop here, I spent two days shooting aerials of Tucumcari Mountain at sunrise and sunset for "Flying Route 66."

In shooting air to ground photography while I’m flying, I keep to a strict routine to minimize the risk. First, I monitor the local radio frequency, in this case Tucumcari Unicom, and give frequent announcements of where I am and what I’m doing. Secondly, I circle the subject noting terrain, wind, obstructions, lighting, and decide from what point I want to shoot. Then I fly a standard holding pattern based on that point, and pick up the camera to shoot a few frames each time I’m in position, which only lasts a few seconds. The rest of the time the camera is down and I am a full-time pilot looking for other traffic and making my radio calls while I fly another circuit. I may stay in the holding pattern for half an hour until I get just what I want. If I choose another angle, I go through the whole routine again. The important thing is to keep everything standardized, unhurried, and smooth with shallow bank angles and no abrupt control movements. With a notch or two of flaps I fly at about 50 m.p.h. indicated (my airspeed indicator is in m.p.h.). If the air is rough I don’t shoot. It isn’t worth the juggling act of trying to hold the camera steady while keeping the airplane at a precise attitude. Besides, a lot of the shots are going to be blurred by the turbulence, anyway. In high density areas near big cities, of course, one should always take along another pilot to do nothing but search for traffic. When I wasn’t shooting, I walked around Tucumcari visiting classic Route 66 landmarks such as the Tee Pee Curios Shop, the Blue Swallow Motel, and La Cita Mexican restaurant. Part of the time I just lay on my back in my room at the Pow Wow Motel staring at the ceiling, and recalling that I’ve been a transient all my life. That’s why I felt completely at home in the Pow Wow. My bag is always packed, and I always look forward to hitting the road in my Super Cub for the next adventure.

Holbrook, Arizona, is one my favorite stops in the Grand Canyon State. The airport runway parallels the former Route 66, now Interstate 40, and you can walk to your motel. The surrounding countryside is beautiful in early morning or late in the day. This is another ideal place to stay a day or two and shoot aerials.

At Seligman, Interstate 40, which covers almost all of the original Route 66 in Arizona, dips to the southwest, and a stretch of two-lane highway still marked as Route 66 arcs northwest to Peach Springs before swinging back southwest to Kingman. This is a beautiful, desolate, moody stretch of road to fly over. From Peach Springs you can look north and see part of the Grand Canyon.

Crossing the Colorado River at Needles, California, I was soon over the Mojave Desert. People seem to either love or hate deserts. I love them. The stark landscape and clarity of the air makes you consider ideas you never thought of before. I photographed scars in the desert left by Camp Essex, one of General Patton’s World War II desert warfare training camps about 40 miles west of Needles near Essex, California. As I write this, I recall that southwest of Essex the old Route 66 almost touches the desert training area of the Twentynine Palms Marine Corps Base where some of our Marines now in Iraq undoubtedly trained.

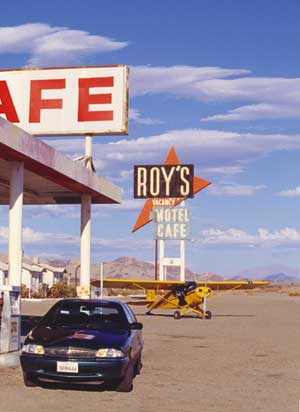

Further along the highway I came upon Amboy, California, which has a population of some 20 souls. It is, however, home to one of the all time classic Route 66 establishments, Roy’s Motel and Cafe. Roy’s has been a landmark on the old route since the ‘30’s, and it still has a "tourist cabins" charm from that period. It is rustic, and you won’t find a color TV nor Internet access in your room, but you will be experiencing the way it was on the open road in the heyday of Route 66. For sky bums, there is a dirt and stone airstrip a few steps west of Roy’s. It is unmarked on sectional charts, and pilots of nosewheel airplanes should be careful to avoid rock damage to their propellers if they decide to land there. Best advice is to call ahead to check on the condition of the strip before landing. Avgas is not available. Otherwise, Roy’s is a delightful place to stop for a hamburger and Coke, or for the night.

Flying westward to Barstow just after sunrise, then through Cajon Pass to San Bernadino and Los Angeles, the clarity of the desert became obscured by the smog of the Basin. Clover Field, as Santa Monica Municipal Airport was originally called, soon came into view. The air was much clearer nearing the airport, and at the Pacific Ocean beach I could see the Santa Monica Pier marking the end of Route 66.

I landed, parked, and sat in the cockpit for a while thinking of all the sights I had photographed on my homage to the open road. If "Flying Route 66" conveys what I have seen and felt, if it takes you with me in the cockpit, I will be a happy man.

|